For the last edition of Sexuality in Color, I interviewed Bianca Laureano, intersectional

sex

educator and general badass, about founding the Women of Color Sexual Health Network (WOCSHN), her

identity

as a sex educator, and what three songs would be essential to her Ultimate Sexy Times playlist. If you haven’t gotten a chance to read the extended interview, I highly recommend it — check out our conversation here.

For the last edition of Sexuality in Color, I interviewed Bianca Laureano, intersectional

sex

educator and general badass, about founding the Women of Color Sexual Health Network (WOCSHN), her

identity

as a sex educator, and what three songs would be essential to her Ultimate Sexy Times playlist. If you haven’t gotten a chance to read the extended interview, I highly recommend it — check out our conversation here.

I was surprised and grateful when Bianca shared her story about what it was like to be grieving and craving intimate touch from people she was close with. She even referred to that experience as feeling like her skin being on fire, which I thought was a totally apt metaphor. She was experiencing what we call “skin hunger” — a very basic human need to feel the comfort of physical touch. She even brought up the fact that babies die if they don’t get touched — I thought I’d take today to elaborate a little on that thought.

Truthfully, there is no study that determined that infants will die if they’re not touched enough, partially because setting up an experiment that could give that kind of conclusive result would be highly unethical (and illegal). However, one of the most frequently cited studies that speaks to this idea was conducted by a man named Harry Harlow at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, using rhesus macaque monkeys. Without going into extreme detail, the study looked at the effects of separating baby macaques from their mothers in infancy.

One particularly famous experiment involved providing the orphans with two “surrogate mothers,” made out of wire and plastic. One of them was fitted with a full bottle so that it would provide nutrients, and one of them was covered in a soft fleece cloth. When the baby monkeys were exposed to the setup, more often than not they would choose to cling to the cloth mother, only visiting the wired mother to feed, suggesting that they valued the comfort and warmth of the cloth mother just as much as (or more than) sustenance. In a later experiment, Harlow found that baby macaques who were given a wire mother with food had significantly more digestive issues than those who were given a cloth mother with food. He interpreted this to mean that a lack of comfort caused psychological stress, which translated somatically in the form of gastrointestinal symptoms. You can watch some videos of these experiments (although as an overly empathic person, I found them hard to watch – they contain footage of baby monkeys not receiving the dynamic comfort and nurturing that they deserve).

But hold up, Al, why are you talking to us about monkeys?

Well, because I’m a nerd, and an armchair psycho-sociologist, but also because I believe it’s important to back up our claims with research and evidence. I could tell you from 100 percent of my personal experiences that I find human touch comforting, and I’m sure that most people would agree, but I think it’s really helpful to look back at the research that’s been done on these concepts (especially when we think about how major social institutions like the government or healthcare system are dependent on this research to provide a framework for their services). And, as I’ve mentioned on this blog before, the entire medical/scientific research canon is built on foundations of institutional racism and unethical behavior. We gotta know where we’ve been to know where we’re at, you know?

If you’re looking for research that centers around actual human infants, a study from 2010 found that when infants’ play with their mothers was interrupted, infants that continued to receive their mothers’ touch as well as seeing her face experienced significantly reduced amounts of cortisol (the hormone associated with stress) in their saliva. This was compared to a control group of infants whose mothers only looked at (but didn’t touch) them when playtime was interrupted. These results speak to the fact that being near people that we love is comforting during times of discomfort, and physical touch specifically makes a difference in how our body manifests stress. It doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to see how these small moments of stress (and whether or not we receive the comforting touch that helps us mitigate them) can build up and have lasting effects on our mental and physical health.

So we’ve established the basics – that human touch feels good. That’s why babies will cry to be held, why children sit in their parents’ laps, why friends hug when they see each other, and why romantic partners touch each other a lot. We use touch as a way to communicate (by the way, the technical term is haptic communication). But there’s more to the story if you think about it a little harder.

It turns out that there’s a whole field of study dedicated to exactly this topic — how people’s expectations around personal space, appropriate touch, and boundaries change across cultures and identities. It’s called proxemics, and I find it completely fascinating. I recently talked with some college students at work about cultural norms and personal space and they brought up some really interesting points about touch, identity, and culture that I wanted to share (with permission).

Patel, who was born in India, told me that in his family it’s a requirement to give each of his aunties a kiss on each cheek when they come to visit, no questions asked. He says that it would be considered rude and disrespectful to his elders if he didn’t stop what he was doing, stand up, and show this display of physical affection when they enter the room. Usually this greeting is followed by them spinning around and tutting while looking him up and down, insisting that he’s too skinny and that they he needs to eat more. He said that he doesn’t mind the cheek- kissing , but feels awkward in those moments when all of his family’s attention focuses to his body’s appearance.

Lina, who is first-generation Japanese-American, mentioned the fact that she was never touched on the head by adults as a kid. When an American teacher ruffled her hair on her way out to be picked up from kindergarten, her father stood there and was shocked. She said they had a huge conversation about it at the dinner table that night, and about how strange it was that the teacher touched her in that way. According to her family, you just don’t do that. Eventually, they realized that the teacher was just trying to be playfully affectionate, but it was a learning moment for the whole family. This was just one of the many ways that Lina felt like she was the cultural translator for her family in navigating American culture and whiteness.

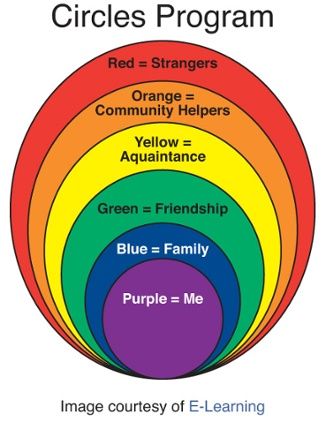

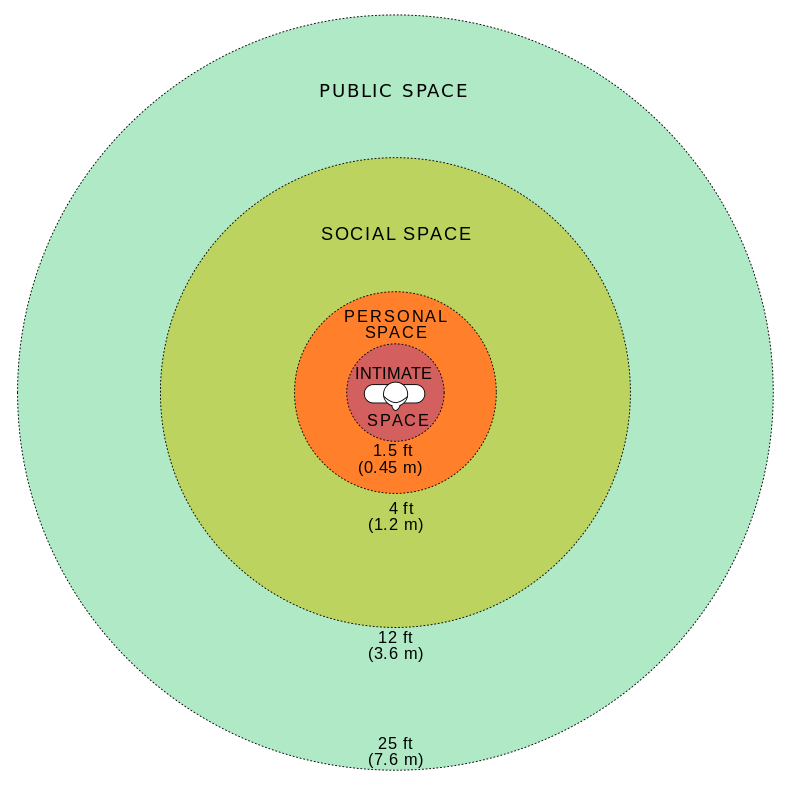

Eric said that one of the first things that he was taught as an autistic kid in special education was “the circles.” Teachers used a set of concentric colored circles to describe the different physical boundaries for different levels of relationships/intimacy. At the center was Eric, in purple, and the next blue ring was for family, then for friendship, etc. This model is actually pretty similar to one used for the allistic (non-autistic) public, developed by sociologist Edward T. Hall, which states that there are four measurable zones of physicality surrounding a person: 1) intimate space: within 1.5 feet of a person’s body; 2) personal space — between 1.5 and 4 feet; 3) social space — between four and 12 feet; and 4) public space — between 12 and 25 feet out. Eric said that when he wanted a hug from someone, he would have to ask if he could come into their purple circle first. He told me a great story about enthusiastically teaching the circles to his mailman by drawing them out with sidewalk chalk.

Marina told me that ever since she was sexually assaulted a year ago, she finds herself craving non- sexual touch. When she was going through the initial shock period , she thought that she would feel more anxious in public, that she would want to avoid being touched and would feel the need to maintain strict physical boundaries. But what she felt was the opposite; Marina described herself as wanting to feel more connected to the people that she knew she loved and trusted, and would find herself reaching out to hold hands, hug, and hang onto friends more. She said that at first her friends were a little resistant, as most of them grew up in typical middle-class white American circles that dictate that close touch is mainly reserved for romantic partners. But that when she expressed her need for a certain type of touch (similarly to the way that Bianca did!), her friends were understanding, and found that their group became much closer emotionally when they allowed themselves to be more physically intimate in a platonic way. Marina said that there was even a moment where she and her best friends were spooning in bed and watching TV together, and she had a moment of pride and gratitude that she was able to speak up for herself and get the loving/caring touch that she needed. Sort of a “Why didn’t we think of this before?” moment.

It's hard to make generalizations about “American culture” because the United States doesn’t have one homogenous culture. How close one might get to someone else’s body in dimly-lit club in Los Angeles is very different from a Walmart in South Carolina, which is different than a college football team’s locker room, which is different than a cross-country airplane flight. There are hundreds of thousands of identities and communities that each have their own beliefs, values, and expectations that translate into physical behaviors and social dynamics. Again, call me a nerd, but I think breaking these cultures down and thinking about how they communicate and conceptualize personal space is really interesting, and it helps inform about how I think about myself within the context of interactions with lovers, friends, acquaintances, and strangers.

It’s also worth thinking about whether or not we like or agree with these rules for interaction, because there could be a whole lot of comfort and bodily autonomy that we’re missing out on. Like Marina’s friends, we may be limiting ourselves from accessing the type of touch that we crave and that helps us feel better when things are difficult, simply because we’re afraid that we will be judged for going against the norm. Conversely, we could be allowing other people to touch us or interact with our bodies in a way that, deep down, makes us uncomfortable, but we let them do it anyway for the sake of “tradition.”

Like I wrote about several weeks ago, preferences about how and when you like to be touched, sexually and non-sexually, are just that — individual preferences. It’s up to us as believers in comfort, community, and consent to communicate proactively about how we want to touch others and be touched. The potential awkwardness of saying “No, I don’t really feel like getting a hug right now,” or “I would really like it if we laid down on the couch together” to our friends can be mitigated if we frame the conversation in terms of personal preference, because at that point, it’s not about reinforcing or defying sociocultural norms, but rather about you getting our own wants and needs met.

What kind of cultural expectations surround haptic communication in your communit(ies)? How do you feel about them? How do they compare to your interactions with peers, or with members of the general public? How does your understanding of your body and lived experiences affect how you think about “personal space”?

Know of a blog, organization, or resource that belongs here? Send it to our curator, Al (that's me!), at al AT scarleteen DOT com.

Interested in contributing as a guest writer for our Sexuality in Color series, or any other part of Scarleteen? Check out our information for writers and then take it from there! Queer and trans writers of color of varied abilities and experiences are always strongly encouraged to apply.